Himatsuri, Kasama’s annual festival of ceramics

No location expresses more the modern identity of Kasama ceramics than the annual Himatsuri festival.

A sprawling tent village that attracts thousands of visitors, the event has roots that are more modest, and came from within the town’s community of individual ceramicists themselves.

2021 saw the 40th edition of the event. With periodic setbacks, it has continued to grow, and attract more ceramicists, musicians, creators and visitors within each period of its existence.

The first festival in 1982 however, had a distinctly improvised feel.

The first Himatsuri had a DIY ethos. Here Kasama Potters Osamu Tsutsui (fourth left) and Mamoru Teramoto (third right) can be seen.

Ceramics in Kasama had been devastated in the 20th century, first by mass produced competition, and then by war. Its revival was enabled by the town’s decision to make itself a destination for individual ceramicists. By the early 1980s a nascent community was in place, influenced by Japanese traditional ceramics, and creative tides since the 1960s.

They lacked however, a focal point. And it was with less than lofty ambitions that the Himatsuri festival began.

Inspired by ceramic fairs they had seen on a trip to the United States, a group of potters including Mamoru Teramoto, and Osamu Tsutsui wondered if a similar get together would be possible in their own town.

They took the idea to the city authorities, who allocated some space. But there was essentially no budget, and the thirty or so participating potters used their own resources in craft to build structures and stalls.

Himatsuri in its early days. An ice cream stand operated by the British ceramicist Edward Sellen can be seen in the left of the shot.

‘I think it was Isobe-san who came up with the idea for the name’ Mamoru Teramoto said in an interview presented as part of the 40th edition commemorations, ‘it was more a case of potters at play, than that we were trying to sell things’.

While Kasama had a collection of potters, it did not have a collective identity, as much had been lost with the passing of previous generations. The first edition of Himatsuri began with a makeshift ceremony in their memory, and in effect a commitment to make a new Kasama-ware, somewhat diverse and unruly.

This said, the original purpose of the festival was also social. Dependent on the elements, and in some years with the feel of a muddy music festival, the potters move between a temporarily created selection of bars and stages, and talk into the night.

The ceramics festival was part sports day

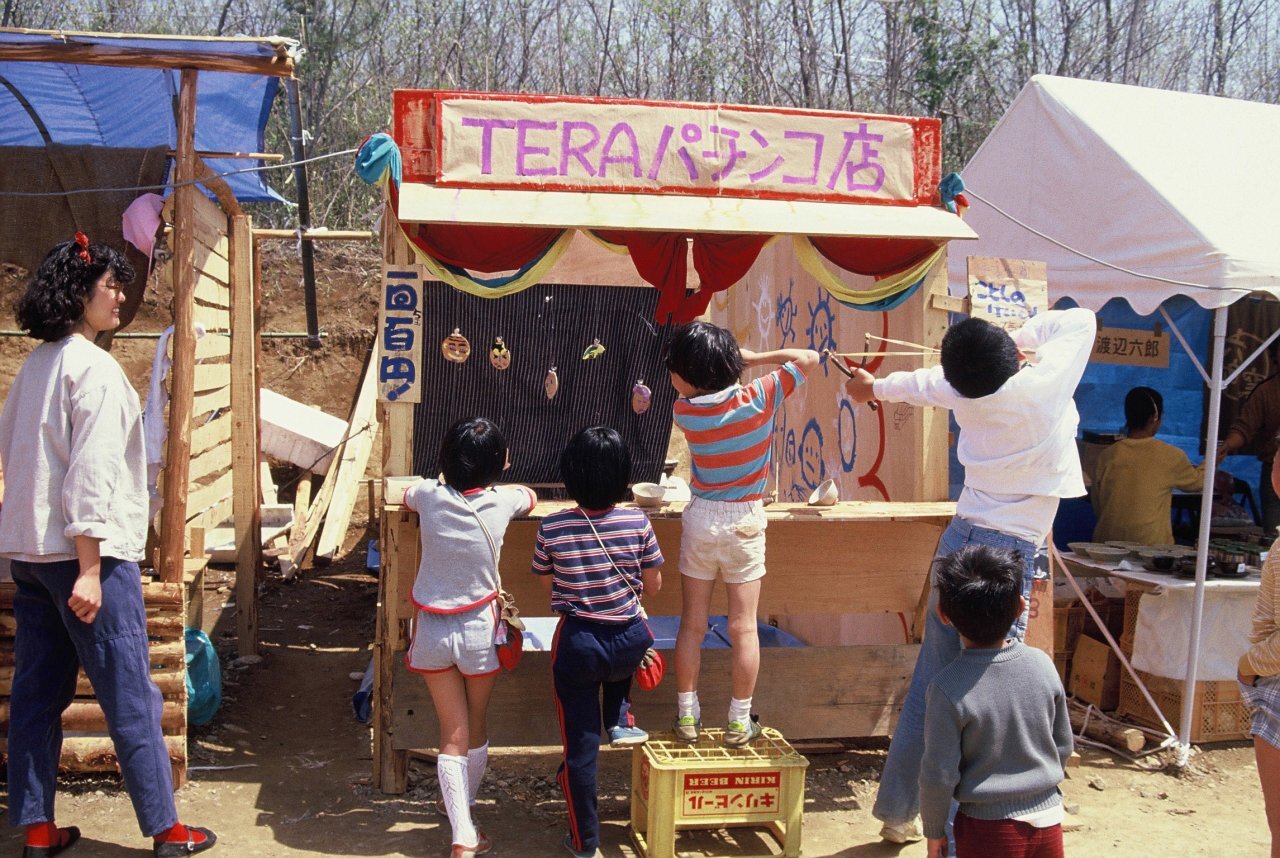

There was even at one point a ‘pottery Olympics’ element, or at least something like a community sports day, with races while carrying the ’te-ita’ boards used to transport pots in the studio. Fun fair style stalls were made to take shots at bisque fired pieces in a ceramic themed version of pachinko, a pinball type game.

Makeshift funfair at an early iteration of Himatsuri

To drum up interest, a tradition developed for the potters to make ceramic masks in their studios, and form a kind of parade through the town to advertise the festival. This added to the colourful sense of jamboree, not to mention the DIY ethos, of the early days of Himatsuri. The potters would also build and fire a kiln at the centre of the event, and their often solo creative process would become collective endeavour for this period in time.

A ceramic mask parade through the town functioned as advertising for the festival

By the early 1990s, the participants had become used to selling their wares to cover the costs of the festival, and the event was taking on some scale. While Japan’s bubble economy of the 1980s had fizzled out, the interest in craft, from both aspiring makers and consumers, seemed to be growing by the year.

From the early days the potters had received strong support from Kasama’s larger and historic kilns such as those today led by Hiroshi Ōtsu, and Kōji Masubuchi - and they too came to play an important part in the story of the festival.

A festival live stage appeared as Himatsuri grew

In 1993 the event moved to larger location, and then again to the current site in the ‘Art Forest’ park in 1995. With a professional stage now in place for performances, and more than a hundred tents offering ceramics for sale, Himatsuri had perhaps lost some of its early improvisation, but not its spirit.

More than just a ceramics festival

It now truly was a meeting place for the ceramic community, and one that attracted visitors from the entire capital region. The clay mask making, originally used in the opening parade, was reinvented as a way to encourage school age children to try their hand at ceramics.

Thirty years into its existence, the event had grown again, now with more than 200 tents. The 2011 edition of the festival was almost derailed by the large earthquake that took place two months before, but in the end it was bigger than ever, with a strong charitable element.

Sadly Covid did what the earthquake could not, in taking out the 2020 festival, but in 2021 the event returned, even if somewhat curtailed in some of its social and performance elements.

Himatsuri is now the largest event of its type in the Tokyo region

Ceramics in Kasama, and ceramics in Japan in general have experienced a revival with the return of the craftsperson. The making process, and the sense of creative community around it, gave Kasama back its wealth.

The dusty tarpaulin and handmade stands of the first edition, with drink and talk, and camp fires into the night - have grown into one of Japan’s most vibrant places for pottery. Somewhere people meet ceramics, acquire the idea to be potters, and see the Kasama ceramic community in its fullest form.

In 2021 the festival ran from late April to early May, with the Kasama Potters of this project in attendance too. This included founding members from 1982, and new faces from the current generation. We also organised a display of work from Stoke-on-Trent in the UK, as part of its recent exchange with Kasama, and as a new source of ideas into the festival’s 40th edition.

Kasama Potter Takahiro Manome offers life performance bar within his ceramic tent

Photos courtesy of the Kasama Pottery Association: https://archive.himatsuri.net/