Rebuilding the home of Kasama ceramics

2022 marked 250 years of Kasama ceramics. This was an anniversary drawn from the origin story of the Kuno pottery works. Not just the cradle of ceramics production in Kasama, the early experiments at the Kuno business had influence across the region. The wide knowledge of this story however, was in contrast to the modern condition of the Kuno works, a situation which a group including Kasama Potters has worked to resolve.

The early days of ceramics in Kasama have much in common with the folk crafts which set roots around Japan in the Edo era (1603-1867). A growing population with an irregular income from agriculture, led people to seek more from their surroundings. Ceramic clay was one treasure in the ground, that with skill, could support livelihoods.

For a period in eighteenth century Kasama the weather was unforgiving, and the agricultural community in crisis. New ideas were needed, and were provided it is said by a meeting that took place in approximately 1772. In the Hakoda area of present day Kasama, village elder Hanuemon Kuno encountered a visiting ceramicist from western Japan. Legend has it that Kuno was able to connect the skills of the visitor to the seam of ceramic clay in the region, and a new tradition was born at the family workshop that he established.

The grave of Han-emon Kuno can be found in the mountains close to the ceramic business he founded

The ceramics made at Kuno were known as Hakoda-ware, and the kiln was adopted as an official supplier to the Kasama domain in 1861. The founder of Mashiko ceramics, Keisaburo Otsuka is also recorded to have discovered his craft at Kuno in the nineteenth century, as its influence grew. A location in history, the works are also a family story, with pottery enduring to the current 14th generation.

This however, does not describe the struggle to keep the business going and the reality that led its physical legacy to fall into disrepair.

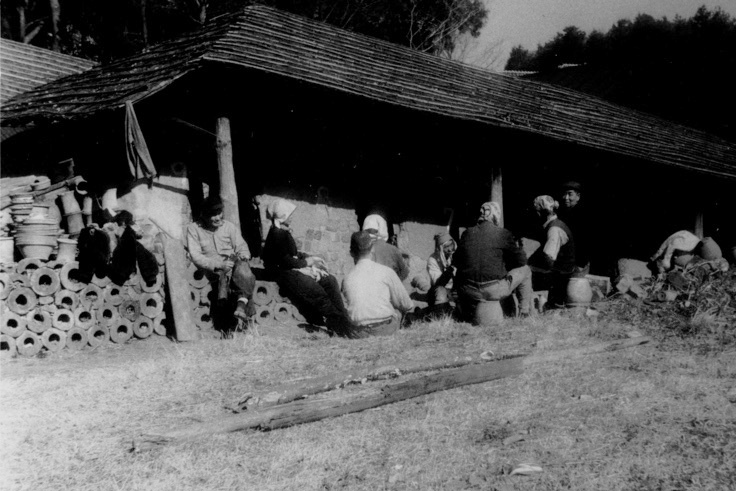

Historic scenes from the Kuno ceramic works

The Kuno works today are an interlocking collection of buildings with some features that would be recognisable to its founder. This includes the 14 chamber climbing kiln that is among the largest in east Japan, the wood lid urns used to rest glazes, the mortar like vessels in which ceramic ingredients were pounded, and the series of potter wheels that line the workshop wall. To create a form of mass production, these wheels were converted to a belt driven system that sped the work of the Kuno craftspeople. But it was not enough to prevent the struggles of wheel created ceramics to compete on cost. Kasama clay was not best suited to ceramic molds, and the challenges to make at scale meant it was time for a new approach.

As a settlement Kasama moved in the post war era to make humans its main resource, with ceramic artists offered incentives to locate themselves. Amid the changing tides, the Kuno works risked being washed away. Beneath its leaky corrugated iron roof the family’s 14th generation, Keiko Ito, felt a weight that was hard to bear. Her father passed away in 2002, leaving the business to her. This was a succession she had resisted, and at one point actively moved away from. But she was drawn back to the now silent workshop, and in a corner of it has practiced as an individual ceramicist. Using the observed skills from her youth to make pots, the building retains corners that have been unchanged as far as anyone can remember. Fragments of old ceramics, pieces of history and a structure that is reaching its limit.

Time took its toll on the Kuno buildings, while the nationally important 14 chamber kiln was damaged in the 2011 quake

While she had succeeded in returning ceramics to Kuno, there were still many setbacks. In repairing some of the inflicted damage from the 2011 earthquake, Ito learned to rely on the people around her. Nevertheless, she was as intimidated to think of the future, as she had been by her legacy as the 14th generation Kuno. Each raindrop through the roof was a reminder that the physical structures of Kuno would decay if Ito did not face the inheritance she had never requested.

A turning point came with the arrival of sculptor Aya Sasakura as a frequent visitor to Ito’s workshop. Someone who spent an early career in sophisticated material manufacturing, Sasakura had relocated to Kasama to build a second one welding and affecting stainless steel into striking forms. She knew what it meant to make a change.

The inherited skill of the Kuno family, as known in Kasama legend, is to respond well when a visitor presents a good idea. So perhaps something triggered inside Ito when her guest suggested that the works could be modernised using a crowdfunding campaign. There had been ideas in the past too, but a difference now was that Ito’s supporters were prepared to form an association to make them happen. The Kuno Pottery Works Preservation Committee, has Sasakura stand alongside Ito at is head, and includes Kasama Potters Kenji Tayama and Takahiro Manome among its members. Launching its crowdfunding campaign in 2022, initial targets were far exceeded.

“When we began I couldn’t quite believe it would work” Manome said. “But the donations show how much the Kuno works means to the area, as the place where ceramics began”

While the committee reached its fundraising goals, it is also true that they had not reckoned with the growth in material costs in the aftermath of coronavirus, and the surprises that would be thrown up by the Kuno buildings themselves. Its foundations are shallow, and it is tilting. The plan had been to reopen the works as a visitor attraction, gallery, cafe and shared workspace in spring 2023. But re-budgeting means the cafe idea is on hold, as is insulation for the roof. The aim remains to complete the reconstruction within 2023.

Work on the roof and upper floor the ceramic works has advanced following the successful crowdfunder.

The story of Kasama ceramics is one of reinvention. In the earliest era pottery was a way for farmers to supplement their income, and escape persistent famine. In the turbulent era of restoration and civil war in the late nineteenth century, Kasama shifted to making ceramic hot water bottles, kitchen mortars and urns that could be used in modernising Tokyo. As cheap plastic replaced clay in the 20th century, the town moved again to become a centre for creativity, and the capital region’s largest home for studio potters. Throughout this time the Kuno works stood as a location to remind how pottery entered the life of the community. The community itself through donation and energy, is now working to rebuild the works as a symbol of Kasama today.

Photographs courtesy of the Kuno Pottery Works Preservation Committee

The Kuno works remains closed to the public while construction work takes place. Progress can be followed at the crowdfunding page, here: https://readyfor.jp/projects/kunotouen